Contents

Search 2.0

The Future of Leadership Appointments

A definitive guide to more-inclusive outcomes

Search 2.0

The Future of Leadership Appointments

A definitive guide to more-inclusive outcomes

Search 2.0

The Future of Leadership Appointments

A definitive guide to more-inclusive outcomes

Is there a better way to select leaders?

Despite the progress made in promoting diversity in leadership appointments across the world, the lack of inclusivity remains a major concern, and we believe it’s time to challenge some of the established practices that have been in place for decades.

Search 1.0, the way leaders are currently chosen and supported, has evolved earlier than and separately from the more recent emphasis on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI). DEI aspirations have been bolted on to Search 1.0—a process that isn’t designed to deliver on them. External pressures and individual efforts have accounted for much of the progress in promoting diversity, rather than the system itself.

Search 2.0 is the new gold standard. Applicable across roles, industries, ownership structures and geographies, it provides societal and situational perspective and conducts an open-heart surgery on each step involved in leadership appointments. With inclusivity at its core, it doesn't exclude any leader or seek predetermined outcomes. It sets the bar for all leadership appointments, not just those focused on diversity enhancement.

Get ready for the upgrade!

Defining DEI

Before diving in, let’s ground ourselves in shared definitions of DEI:

Diversity is linked to difference and variety and how they affect the way we think, behave, cooperate and relate to one another. You can only be diverse in relation to someone else. The sources of diversity are a mix of factors linked to our inherent makeup, qualities, individual circumstances and life experiences. Structural shifts, such as globalization and trade, have created untold wealth in the world but have also unleashed forces that make diversity both more visible and more precarious (e.g., dismantling of local customs, educational systems, languages and ways of life). Each society has norms and priorities about who is considered diverse, and these evolve with the passage of time and changing circumstances.

Equity is a relatively new entrant in management vocabulary and is often used in contrast to equality. Equality aims to create fair outcomes by providing equal opportunities to everyone, while equity acknowledges that different circumstances may require different accommodations to achieve fairness. We prefer to see these terms as a continuum, with balance as the objective. Over-indexing on the side of equality could disproportionately favour those who are best positioned to secure opportunities, while over-indexing on the side of equity could damage the legitimacy of decision makers and lead to disagreements about who is most deserving of additional support.

Inclusion is the act of valuing differences and enabling everyone to bring their distinctiveness to, and thrive in, any situation. It is also about encouraging a sense of belonging, without the pressure to conform. It is the desired state to unlock many of the potential benefits of diversity for individuals, organizations and societies. However, the greater the diversity of a team, group, organization or society, the more challenging it is to achieve inclusion since individuals have less in common with one another. If a culture is not inclusive, diverse individuals may feel like they don’t belong and are forced to conform to dominant cultural norms at the expense of their individuality.

There isn’t a clear answer about what the optimal levels of diversity, equity and inclusion are. However, they should and do evolve over time.

Anatomy of Search 2.0

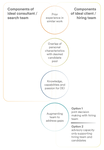

A search can typically be deconstructed into four categories of activities, consisting of 20 steps that determine its outcome.

Choices are consciously, unconsciously, or subconsciously made at each step that can influence outcomes in ways both big and small.

The four main categories are:

Evaluating Candidate Databases

Most search firms have an ever-expanding database of individuals, driven by the explosion in computing power and the availability of data and information. These are complemented by public databases and subscription-based databases. True differentiation comes from the connectivity between these data pools and from deploying intelligent processing tools (increasingly, artificial intelligence and machine learning), and distilling the information into insights that add value in a search—without compromising individual privacy, choices and freedoms.

Every client should test their consulting firm’s practices and capabilities in candidate database management (or their own, if not using a consulting firm), especially the quality and resilience of the search and sorting engines. How is the power of the data channeled to serve you, the client?

Candidate Databases

The Impact of Candidate Access and Consulting Firm Culture

Distinctive candidate access goes beyond the ability to reach a candidate to differentiated non-public insights about candidates that can only come from the credibility, intimacy and trust that has been built up over time by individual consultants within a firm. The ability to share that access with their colleagues and clients in the most value-enhancing and responsible way is what makes the difference between knowing of a candidate and being able to bring them to the table to discuss an opportunity.

Previous experience can be a double-edged sword. Using a firm that has done similar work before allows for differentiated access to the talent pool for a particular search as well as a deeper understanding of “best in class” clients, candidates and trends for a particular role. On the flip side, having strong credentials can create an “off-limits” issue—a firm not being able to access a particular leader or set of leaders because a prior or ongoing business relationship prohibits this access. Unless a search firm has contractually agreed not to identify candidates and informed a client accordingly, a client should always be within their rights to ask for the identification of such candidates and to try to approach them directly.

Equally important is how the consulting firm is set up financially. How do consultants get paid for individual assignments? For example, do they get paid commissions, and does that create natural conflicts of interest in their willingness to share insights on candidates with colleagues? If so, how will these conflicts be surmounted? How do the annual performance awards and profit-sharing mechanisms work? What serves your interests more in any given situation as a client? Clients must recognize the impacts of culture and systems on candidate access.

Candidate Access & Consulting Firm Culture

Consultant Team Composition and DEI Sensitization

In addition to prior experiences, two further factors should drive team composition:

Personal characteristics of the individuals on the consulting team.

Research has shown that access to and acceptance into networks that share a certain characteristic (e.g., gender, ethnicity, sexuality, disability, age, socioeconomics, national identity, regional identity, religious identity, etc.) is positively correlated to possessing that characteristic yourself. The term for this in sociology is homophily, which is the tendency of people to seek out those who are similar to themselves, more than they would typically seek out those who are not similar. (This is also linked to cognitive biases.)

If you are looking to enhance access to and relatability with a particular underrepresented candidate pool, having members of the consulting team who share that characteristic could be beneficial. Though research on this is at an early stage, current Egon Zehnder analysis shows that female consultants on average end up presenting more female candidates for interviews than male consultants do. Searches led by female consultants outperformed searches led by male consultants by 25 percent in terms of presenting at least one female candidate to the interview stage across the firms’ global searches.

Nature & Nurture

Personal characteristics of the individuals on the consulting team.

Those who engage seriously in the DEI dialogue irrespective of their personal characteristics seem to fare better in the diversity of hiring outcomes. Current Egon Zehnder analysis has found a positive correlation between engagement in DEI knowledge, language, capabilities and participation and a higher proportion of diverse hires. Consultants who are designated as DEI champions made 20 percent more female candidate hires than the wider consultant pool, irrespective of their gender.

The ideal team composition is one that has sufficient experience, the desired personal characteristics, and sincere passion, knowledge and capabilities in DEI.

The DEI conversations of the future will require more nuance and an ability to handle greater complexity. Over time, diversity definitions will move beyond thematic asks on gender, ethnicity and sexual orientation toward more comprehensive and inclusive approaches and definitions. No individual consultant could hope to have personal characteristics to match those definitions.

Client Team Composition and Client Team DEI Sensitization

Egon Zehnder analysis shows that if more than 40 percent of the client team is female, there is a 40 percent or more chance of there being a female hire on the project. The sweet spot seems to be a client team that is 40-60 percent female, which roughly equates to 47 percent female hires. (On the other hand, 80-100 percent female client teams equate to about 40 percent female hires, and 0-20 percent female client teams equate to 29 percent female hires.)

Additional factors come into play when the client hiring team is not diverse and does not have a successful track record of attracting and integrating diverse talent onto the team. In such a case, we’d recommend providing additional support to the client team and bringing different client voices (beyond those directly involved in the hiring decision) into the decision-making and influencing structures from the get-go.

There are two ways to structure this support:

- In the foreground (part of the interviewing, project management and decision-making process)

- In the background (in an advisory capacity)

Though the former, more “direct action,” support may seem more impactful and tempting, tokenistic inclusion without long-term investment in the success of a diverse hire can do more harm than good and feel inauthentic to candidates.

The extent of any involvement needs to be thought through. The objective is to act as a bridge to deeper appreciation of diverse candidates, picking up on subtleties and bringing differentiated perspectives that may aid better decision-making and relationship-building, without hijacking the process.

Finally, it is worth emphasizing the advantages of pursuing DEI goals in a team construct. While team members will bring their individual biases, they are likely to be different from your own and could lead to better discussions and outcomes.

The Search Strategy

Honing the search strategy is a critical step. Consultants must not expand the search criteria too much to avoid unnecessary confusion and wasted effort, but not contract it so much that candidate choices are restricted. The collective result is a search strategy that is often more precise and prescriptive than it needs to be. This can hinder the DEI outcomes of a search because diverse candidates are underrepresented.

Take a search for the CEO of a company in the oil and gas sector, with over £1 billion in revenues, headquartered and publicly listed in the UK, as an example:

- If the search strategy is designed to hit each of these five criteria (oil and gas experience, revenue over £1 billion, prior CEO experience, prior publicly listed company experience, prior UK headquarters experience), just one female candidate would make your list. Now, let’s flex the search strategy to expand the pool of female leaders who could be a fit.

- Relaxing just the geographical criteria to include Europe and North America would give you four female candidates, extending to seven if you include the rest of the world. Depending on the degree of flexibility the client is willing to deploy, by relaxing just the geographic criteria alone and nothing else, we have managed to enhance the number of female leaders by 700 percent.

- Now, let’s assume that the client situation does not allow any flexibility in geographically expanding the search criteria because being UK-headquartered and having experience in a UK-listed company is deemed critical. Relaxing the sector criteria in that instance, while keeping everything else the same, could give you 17 female leaders to consider, an increase of 1,700 percent.

- A hybrid flexing of criteria is also possible. Say the client is unwilling to compromise on oil and gas experience, publicly listed company experience and the scale (revenue) of the business. However, they are willing to partially flex on geographical criteria (e.g., consider Europe in addition to the UK but not any further, and may be willing to consider any current C-suite leaders as opposed to just CEOs). Even this limited flex on just two dimensions (geography and seniority) dramatically increases the number of female leaders that you can consider to 25, an increase of 2,500 percent.

Flexing our search criteria may lead to two main counterchallenges: First, these leaders may not all automatically be realistic candidates. It’s too early in the process to make that judgment and would be akin to ruling out options before knowing what they are. Second, some may argue this practice leads to “positive” discrimination. However, this would not be discriminatory if the underlying philosophy were applied to all underrepresented pools to ensure that the long list had a good overall representation (i.e., inclusive, not exclusive, in its approach). For overrepresented groups, tighter criteria are justified, as they would be sufficiently represented on a long list anyway. If they are not sufficiently represented, the expansion/relaxation of criteria to an appropriate level ought to apply to them as well.

Flexing the search strategy criteria

Crafting Effective Role Specifications:

The Importance of Clarity and Inclusivity

Often, the starting point of substantive candidate interactions is a role specification. If done well, it can attract the best candidates. But if done poorly, it could alienate them. Apart from extraordinarily high-stakes appointments, where the role specification goes through a formal creation and review process (most notably during CEO successions), they are often hastily compiled by either the consultant, client, or both.

Role specifications don’t need to be works of art, but they need to withstand scrutiny and generate excitement. Good writing that conveys clarity of thought, passion and empathy, and an accurate and compelling vision, is the most important differentiator. A good role specification should include the following:

- Information that gives the reader an understanding of the past, present and prospects of the organization.

- The organization’s vision, purpose and values.

- It should set the scene that has resulted in the creation of the leadership opportunity and set the role within the organizational structure and reporting lines.

- It should describe the objectives of the role and elaborate on the experiential, competency and personal criteria that will drive candidate evaluation and choice.

- It should finish with important administrative details, such as the role location, travel needs, opportunities for hybrid working and other aspects that may be material to raising and ascertaining candidate interest levels.

We recommend circulating your draft role specification between the consultant and client teams, soliciting input, and expanding this circle of input if the teams are not diverse themselves, with the overarching goal of ensuring that it is pitched correctly in terms of the candidates you want to attract.

You may receive feedback along the lines of “female leaders may not respond well to this characterization,” “non-native English speakers may not fully comprehend the meaning of this section,” “the role specification is too rational and lacks emotional resonance,” and so on. This does not mean that the commentary is correct in every instance. Readers have biases just as much as writers do. But it is still worthwhile to do this, as it gives you a glimpse into how information is processed differently by different people.

It is important to note that cognitive biases can flow through writing styles, for example, by choosing masculine forms of words (e.g., he/chairman). Some words may trigger others, evoke an emotional reaction or cause offense. However, being overly cautious about the use of language doesn’t aid good writing or the DEI cause. Overenthusiastic DEI policing can create documents so devoid of expression that they create a deflating rather than uplifting experience for the recipient. As your knowledge of DEI improves, it is possible to mitigate these risks.

“A camel is a horse designed by a committee,” as the saying goes. Don’t crowdsource the role specification; retain primary authorship with one person and acknowledge the feedback and integrate what feels appropriate.

Two Cardinal Rules of Engagement

Every client and consultant team that is sincere about DEI should have no problem agreeing to two cardinal rules, but these are trickier than most people imagine.

Rule 1

A client interview process should not commence unless the candidate slate is diverse.

What diverse means will be situational to each client. Agreeing to this step is an essential moment of truth. Not as a roadblock, but as an iterative dialogue between the client’s diversity objectives and the search strategy—one or both may need to loosen to propel a search toward intended outcomes. Multiple iterations of the search strategy may reveal that a client has reached the limits of the flex they can offer in expanding the search criteria. Candidate feedback may also reveal that clients just don’t have the culture or the market reputation to attract the candidates they seek. This dose of realism may be a bitter pill to swallow, but it is ultimately the right approach, and it may be necessary to reset ambitions to more achievable levels as a result. On the other hand, it could be the case that relaxing the search criteria gets the diverse mix of candidates you seek.

Rule 2

No active or positive discrimination on ethical, moral or legal grounds.

Especially in the United States, Canada and the UK, senior leadership recruitment is treading on dangerous ground, with mandates to only hire individuals from underrepresented minority groups into certain roles. Ironically, the most discriminatory requests are often for chief diversity & inclusion officer searches, where clients feel obligated to not appoint a man and not even a white woman into the role on account of the message that would send to the organization. If this is what DEI championing is coming to, there is a need for greater introspection on the part of DEI proponents. Clients are understandably under tremendous pressure to act on diversity, and consultants are under tremendous pressure to respond and provide solutions. External pressures from various governance groups, shareholders, employees, stakeholder groups and the media are also significant. The collective result of these pressures could be active discrimination against majority groups and positive discrimination in favor of desired minority subgroups on individual search mandates. Consultants and clients know this all too well. Implicitly or explicitly, discriminatory mandates are not documented and at best are alluded to as preferences to avoid acknowledging what they truly are: discriminatory.

In some instances, it may be tempting to justify it as acceptable collateral damage to fair and due process or the only route to progress in a system where the odds have been stacked against underrepresented groups. However, if you cannot document a preference explicitly or cannot say to a candidate openly that they are being interviewed or not being interviewed precisely for a personal characteristic they do or do not possess, you are falling foul of the spirit of DEI—and most likely also of the law of your land. A short list of 100 percent ethnically diverse candidates or 100 percent female candidates does not qualify as a diverse short list, nor is it an inclusive act.

All hope is not lost. Egon Zehnder analysis shows that if a short list is diverse, it materially increases the chances of a diverse hire. For example, our analysis shows that having just one female candidate on the interview slate creates a 30 percent chance of a female hire, increasing to 45 percent when there were two and 60 percent when there were three.

Victory claimed on the back of discriminatory practices by DEI champions is detrimental to long-term legitimacy. Once you discriminate in favor of a particular minority group, you don’t just discriminate against the advantaged majority group; you also discriminate against all the other disadvantaged minority groups you fail to consider.

Establishing clear rules for your search strategy

Anti-Bias and Inclusive Candidate Profiles

In the early stages of a search, one-page summary candidate profiles are the industry standard. They are the starting point for comparing and prioritizing a long list of candidates toward a shorter list of the most promising ones to actively start contacting.

A review of global practices revealed that typically at least seven, and up to 10, pieces of information get explicitly or implicitly revealed about the candidate on these profiles (photo, name, age, nationality, location, languages spoken, educational qualifications, executive roles in reverse chronological order, non-executive roles in reverse chronological order and compensation). Both in terms of layout and content, the status quo is problematic.

On layout, most of us are trained to read from left to right and from the top to the bottom of a document. Where things appear on a page and how much attention is given to them is an active choice and does have consequences. The most crucial information about a candidate should be toward the top left of a profile. If it isn’t, it can lead to disadvantages against candidates based on information that is less relevant or irrelevant for success in a role. For example, age, nationality, location, photograph and languages spoken often appear before and above the most recent work experiences, while the latter should have the most weight.

Let’s unpack the main components of a candidate summary.

Headshot

Age

Nationality and current location

Nameless/Anonymize

Language skill

Compensation Disclosure

Education qualifications

Career history

Click on each section of the summary to learn more

What is the candidate’s headshot serving at this stage beyond encouraging biases, which could include favoring those with more conventionally agreeable and attractive features? Some might argue that showing a photograph is a convenient way to imply racial and gender diversity without having to “say it.” However, there are other, better ways to ensure diversity without resorting to photographs. Attractiveness bias is a risk at the interview stage anyway, but it is easy to avoid at this stage by withholding photographs from profiles.

Age, which is either directly recorded, as allowed in some countries, or can be easily guessed through the listed year of graduation. Whether obvious or subtle, this perpetrates the age discrimination that is rampant in senior management discussions today.

Unless it is relevant to the ability to accept a role, information regarding nationality and current location does not merit a place on the top left of a profile, and depending on the purpose they are serving, should either be left out completely or relegated to the bottom right of the layout.

There is an argument to be made for candidate profiles to be nameless/anonymized. While there may be merits to this argument, especially for entry-level, mass-recruitment roles, it is not the best solution in senior management settings unless there are strong grounds to believe that actively discriminatory factors are at play and that using names could make the situation worse. Anonymizing names in senior, more bespoke, low-volume settings can dehumanize a discussion, make it unnatural, be distracting and can crucially reduce the quality of the dialogue about the candidate between the client and the consultant.

Language skills are a legitimate line of inquiry. Both the client and the consultant should be clear on whether fluency in multiple languages is crucial to succeed in the role before including them. In any case, they are unlikely to be the most important criteria for any role and should find space only at the bottom right of the page.

Regarding compensation disclosure, data protection regulations prevent compensation information from being recorded on a candidate profile in most countries. And while this information is highly relevant to the ultimate workability of a candidate, it may not be valuable at this stage of the process. Our recommendation is that compensation details shouldn’t be included in candidate profiles, even if allowed by law. For instances where clients insist on this information, and are legally allowed to seek and record it, prudent data management will still dictate that this information ideally be communicated verbally. Recording this data in electronic communications may not be fully secure and may pose a risk that people not directly on the team can access it.

Education qualifications can to some degree signal quality (e.g., reputation of university), relevance (e.g., knowing that a candidate is a Ph.D. in a subject that is core to the client’s business), and achievement orientation from a young age. The key is ensuring they don’t receive disproportionate prominence. There is no justifiable argument for someone’s education qualifications to be placed above their recent executive career in the hierarchy of how information is conveyed or discussed. It places prominence on outcomes from two or three decades ago as compared to more recent progression and achievements. In addition, graduation years should be avoided as these are a well-trodden backdoor to approximating age.

Career history, including executive and non-executive experience, is by far the most important information about a candidate and should be clearly highlighted in the candidate profile. The reverse chronological order of the most recent experiences first and providing the location of each of these experiences is valuable and should be included. Ensuring that only the most relevant and material roles are included (irrespective of whether they elevate or hinder someone’s candidacy—a bad career decision would still classify as relevant and material) reduces clutter and improves focus. Enforcing a cut-off in visible dates for roles far back in one’s career can also be introduced to eliminate any final vestiges of age bias. For example, for all candidates across a long list, the last 20 years can be detailed more precisely, while anything beyond 20 years ago can be quoted in summary, without mentioning dates, while including basic helpful information in terms of the companies worked for, location and types of roles.

Adjusted for all of the above, your new, improved one-page candidate profiles are largely unbiased and focus on key decision-making criteria for candidate prioritization.

Taking profiles to the next level includes bringing information from publicly available sources, complemented by data sourced with the approval of the candidate, that brings to life aspects of their diversity and lived experiences that may otherwise not be apparent or visible, but could be beneficial and differential to the client. This also helps highlight aspects of their personality and diversity that are not possible to capture otherwise in a professional experience narrative. Each candidate profile could include a personal commentary section with the understanding that these insights and information will be further enhanced during a project.

There are two caveats to this recommendation: First, depending on the nature of the personal candidate information, verbal rather than written commentary may be best, even if you have the candidate’s permission to disclose. Second, if this information is not available on everyone in the candidate slate, it can lead to inconsistencies and potential bias against those whose personal information is lacking. On balance, we’d advise including personal commentary on profiles only if it can be consistently documented without risking embarrassment or distress to anyone.

The Role of Diversity Statistics

If a client wants to attract a specific underrepresented category to a position, the tracking of diversity statistics—and what markers to track (or the best proxies for those markers)—should be discussed by the client and the consultant. Progress updates should include these data on a rolling basis so their evolution can be monitored and corrected as necessary to avoid candidates falling off the radar.

At early stages, directional statistics based on logical assumptions are better than having no data, as long as assumptions are not attributed to specific candidates without their approval. As engagement with candidates deepens, assumptions must be replaced with accurate information to ensure the candidate has agreed to be considered diverse before any diversity categorization is attributed to them. This is not always immediately possible. As a result, midway through the search, the quality of diversity statistics may appear to deteriorate. This can be addressed by creating a psychologically safe space to discuss diversity and by obtaining candidate permission. If a candidate refuses or delays categorization, this does not mean they should not be interviewed or are not diverse. It is important to keep an open mind, track statistics early and regularly update them as new insights on candidates are gained.

Diversity Statistics

Expanding the Definition of ‘Lived Experiences’

“Lived experience” is intuitively understood as an individual’s story, and understanding it is a promising pathway to explore what an individual would add to the diversity of teams and organizations. It is defined as:

The firsthand or direct experiences of an individual, which give them unique knowledge, insights and perspectives that individuals who have not had those firsthand or direct experiences would typically not have.

The executive search profession and most clients are adept at exploring professional lived experiences. The need now is to expand the definition of lived experiences to cover a larger time span—from birth to today—spanning both their personal and professional life.

Getting this holistic understanding of a candidate’s personal defining moments is not easy. It takes trust and a psychologically safe environment that is built over time. While the profession (including consultants, clients and candidates) is several iterations away from embracing lived experiences in an integrative way, there is only upside to considering them as part of a search process, priming the system for greater impact over time.

The next step is understanding how those lived experiences inform the individual’s perception of the world around them, how they approach a situation, how they make decisions, form relationships and build alliances. Distilling the information on lived experiences into leadership insights around the individual is a step that could constitute the next frontier of this effort.

The final step is to appreciate the power these lived experiences will have within the setting that this new leader will enter, alongside other leaders and their own lived experiences. Without a grasp of the entirety of the lived experiences on a leadership team, it is hard to understand collective strengths and gaps, and even harder to determine when a particular aspect of someone’s lived experiences should be called upon to enhance the quality of a collective decision. Leaders already do this in terms of professional lived experiences. For example, good leaders will know which member of their team to deploy, to rely on or to seek advice from for a particular business situation. Over time, they should do this with increasing confidence on the entirety of lived experiences. That is when the true power of diversity will be unleashed for the greatest common good.

Lived Experiences

Maximizing Candidate Engagement Strategies

“Lived experience” is intuitively understood as an individual’s story, and understanding it is a promising pathway to explore what an individual would add to the diversity of teams and organizations. It is defined as:

Top diverse talent is in exceptionally high demand, and it’s important to reflect on what makes a client distinctive and appealing to diverse candidates. Just as a company is getting to know a candidate, the candidate is learning if the company is a good fit from a career and skills perspective, and a cultural one. The situation is of course different for an internal candidate. Here, familiarity with the client and its culture may be less of an issue, although there still may be some anxiety, for example, if this is the first time a glass ceiling is being shattered at a particular level of the organization for an underrepresented minority candidate.

Seen from a client’s perspective, there needs to be recognition that simply being a net importer of diverse talent is not a viable or responsible long-term strategy. Every organization needs to play its part in the development of diverse talent pipelines of the future, and as part of that, they risk losing some of their best diverse leaders to better or faster career progression opportunities outside of the company. The cultural and reputational benefits of being regarded as an exporter of diverse talent (and not just as an importer) outweighs the short-term pain caused by the export. It is only through this collective action and the spirit shown by multiple companies that both the quality and quantity of diverse talent pipelines will change in more sustainable ways.

Within a search, support to all (not just diverse) candidates should broadly be in three areas:

- Positioning the role in the most honest and compelling way. This goes beyond the role specification and extends to an open discussion on the different perspectives, criticalities and trade-offs that were discussed in its making. For every candidate, knowledge of the entirety of the client objectives, including on DEI, helps frame their preparations and expectations.

- In-depth discussion both on the client’s decision-makers and on the culture. Understanding the personalities involved, their attitudes, priorities and backgrounds, makes a difference, especially to candidates who might find the characters unfamiliar. Understanding the client’s culture can help a candidate ensure that it resonates with their own personality and professional aspirations and lends itself well to a long-term stint with the company.

- Fine-tuning the interview approach. For individuals who meet the criteria on diversity, avoid overplaying the diversity elements or you risk them becoming overwhelming and one-dimensional. At the same time, don’t underplay them to the degree that they stay superficial or remain unspoken. All candidates, regardless of their background, should be prepared to discuss the full range of criteria required by the role specification and be willing to go to the depths of each criterion (including on diversity). Even for candidates who do not meet the diversity preferences, this mindset is crucial, as it allows them to share their own distinct lived experiences in a way that the client may find compelling, which may also turn out to be underrepresented in a client setting.

Candidate Engagement

Best Practices in Candidate Interviews

A good interview process at the senior level must cover a range of topics: personal background and lived experiences, business experiences, key achievements, competencies, future potential, identity, personality traits, purpose and confidence. Consultants should be challenged to demonstrate thorough interviewing along these lines before presenting candidates. The outcome of this consultant evaluation should be documented in a confidential report that assesses each candidate based on the agreed-upon interview topics, including concerns, gaps or areas to further probe.

The past two decades have seen an explosion in career choices and pathways that make the comparison of experiential journeys between candidates increasingly unreliable as a decision-making tool. A promising assessment is on future potential, evaluating for curiosity, insights, engagement and determination. Egon Zehnder analysis has shown this assessment to be positively correlated to future progression potential. This framework is distinct from prior work experiences and offers the possibility of equitably levelling the playing field in evaluating a diverse slate of candidates for a role. This can help avoid the vicious circle of not hiring underrepresented diverse candidates because they have insufficient prior work experience on account of being underrepresented.

Biases can occur throughout a search but may become acute during an interview process, for example, affinity bias, which favors candidates who share characteristics with the interviewers. This is not restricted to gender, ethnicity, nationality or sexual orientation. It extends to a variety of factors, including attending the same school or university, working in the same company, growing up in the same city, liking the same sports team, etc. This bias can put underrepresented candidates at a disadvantage as they are statistically less likely to share multiple characteristics with the evaluators. Underrepresented candidates may also have had life circumstances that caused them to spend a disproportionate amount of energy and time fitting into majority cultures, communities and organizations, and their formative experiences may have changed their self-image and ways of interacting with the world. It is also likely that for an equivalent position, a candidate who is underrepresented would have had to face a more challenging route to the top that ought to be factored in, demonstrating enhanced resilience or determination.

Clients can rely on a mix of “this is what I have done in the past” and “this is what I think this situation demands” to determine the content of their interview. The location of client interviews (e.g., hybrid, in person, virtual), having familiarized yourself with the candidates’ confidential report, the number of rounds, the gap between rounds, the time given to each interview, panel versus individual interviews, should different aspects be covered in different rounds, should different interviewers cover different aspects, all are pieces of the puzzle. Egon Zehnder recommends creating an interview guide linked to the role specification that provides a framework to guide the interview This guide ensures that all interviewers cover the same minimum set of questions while still allowing for interest areas of the individual interviewer. The consequences of not having a guide are that you are likely to end up with fascinating pieces of insight about a candidate, but these are unlikely to be comprehensive, consistent and in sync with the requirements of the role specification. They make it hard to calibrate the relative strengths between candidates. This creates a vacuum in which decision-making can become overly reliant on individual impressions of candidates and removed from the stated requirements of the role. It can also impact DEI outcomes and be more prone to individual biases.

Challenges and Strategies

for Effective Candidate Calibration

Calibration meetings are a regular feature of most senior searches, and they follow a loose script of each interviewer sharing their interview findings and impressions with a mix of helpful but often incomplete perspectives. At this stage, the list of interviewed candidates quickly breaks into two—most of the list unanimously gets ruled out quickly, and a consensus typically develops around one leading candidate. In a small number of cases, a strong alternate candidate could emerge.

Awareness of potential biases is particularly important here. The “boss” or the “loudest voices in the room” can often quickly and conclusively sway a discussion, and so could other aspects, such as obsessing about a candidate’s minor negative point while ignoring all the other strong aspects of their candidacy. The list of potential individual and group biases at play could be enormous, which is why consultant and client teams should hold a brief session on biases before the calibration session.

Beyond this, injecting a modicum of discipline and a mindset shift in how these calibration discussions are conducted is important. The creation of a calibration guide reminds interviewers of the range of selection criteria that were detailed in the role specification, rather than focusing on a narrower set of arbitrary data points for selection. This allows for a more comprehensive discussion of trade-offs and candidate comparisons against the criteria originally agreed to by the selection panel. Attendees should prepare their summary calibration and preferred candidates individually before entering the meeting as a reminder to themselves of their own independent views. This could allow for a richer debate on differing views, rather than a common, dominant view quickly emerging during the meeting.

Two issues could arise if this is not done.

- Securing diversity becomes the overwhelming tone, leading client teams to discount other vital pieces of information that can drive success in the role.

- Vital experiences become the altar at which many a diversity objective gets sacrificed as collective risk aversion kicks in.

Accepting that there will invariably be biases that drive us toward certain outcomes and giving the process a chance to correct these through inputs from referencing and psychometrics is a better approach then prematurely preferring a candidate.

Calibrations should ultimately lead to candidate rankings, not eliminations. This is not a spreadsheet exercise. The objective of calibration is to ensure that all important factors are being discussed. It is not to deconstruct individuals into basic factors and add up their individual scores. Humans are a package of all those quantifiable and unquantifiable factors, and calibrations should support informed decision-making and reduce biases, not substitute accountability and leadership judgment over decisions.

We encourage clients to not stick solely to the script of what was said by the candidate in the interview. What were your own intuitions as individual interviewers? What were the nonverbal cues that you picked up? What made you curious? What made you nervous? Our intuitions and analyses are both impacted by biases. Tabling them and discussing them as part of the group help you confirm or reject these aspects with greater confidence, as other interviewers similarly provide their own perspectives.

Effective Referencing

Referencing—confirming the educational, career qualifications and other material claims on the CV—is an effective way of checking if a candidate has the leadership experiences and reputation to succeed in the role. But it misses other critical pointers of success such as purpose, identity, confidence, style, diversity, lived experiences, personality traits, cultural factors and derailers.

One of the main challenges with referencing is confirmation bias, which is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor and recall information to confirm prior beliefs about an individual. This risk is especially high when a candidate is the clear front-runner for a role, and the client and consultant team are invested in hiring them.

Confirmation bias can be mitigated by pre-referencing on multiple candidates along the way, and some even before an individual is engaged in the process. Pre-referencing also carries some risk, as it is subject to anchoring bias, which is the tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information encountered. Once a candidate is engaged as part of a process, trust now becomes a factor in taking any further references. With a “live” candidate, references should only be taken in consultation with the candidate. It is important for a candidate to know that neither the consultant nor the client would go “behind their back” in taking references that could cause embarrassment or break confidentiality.

For diverse candidates, we recommend an altered referencing approach that covers a diverse pool of referees over a wider span of time. Because they may have experienced more profound identity shifts during their personal and professional lives due to the pressure to fit into their surroundings, understanding their personal and professional journey and evolution, and getting to the core of what makes them tick and what makes them different, are well worth the effort.

Final detailed references should be conducted at the end of the hiring process, when a particular candidate has emerged as the preferred choice. Excellent referencing requires experienced interviewing and trained listening and observation skills to pick up on both verbal and nonverbal cues. It should only be conducted by individuals, ideally more than one, who have the experience, curiosity, time and acute listening skills required to gain both a depth and breadth of understanding about the candidate, while avoiding the natural pitfalls presented by biases.

Benefits and Limitations of Psychometrics

Compared to referencing, psychometrics is a newer and underutilized option in search. When used effectively, they can provide deeper insights into candidates. However, it’s important not to use psychometrics as a decision-making tool or screening test that labels individuals as having “less desired” or “more desired” traits.

What is important is whether your consultant team has a clear philosophy on what they are trying to achieve through these surveys, whether they are trained in their application and how they hope to tie the insights back to informing the wider candidate evaluation.

There are even greater benefits of candidate psychometric surveys when discussing them in relation to the psychometric profiles of the individuals whom the candidate will interact with if they accept the role. The surveys take less than an hour to complete, and results are stable over extended periods, so they need to be administered only occasionally rather than during each hiring process.

Crafting Inclusive

Terms and Conditions (T&C)

A typical offer combines both financial and nonfinancial criteria. When making a financial offer—base salary, bonuses, long-term incentives, pensions and other allowances—it’s critical to ensure there is no pay gap on account of diversity. A diverse candidate, either because of a relative lack of knowledge about the company or having a different cultural attitude toward negotiation, may be willing to accept a compensation package that puts them at a disadvantage. In many Western countries, there are growing expectations that organizations disclose and address pay gaps. In countries where these expectations don’t exist, committing to pay parity at every level and eliminating anomalies and disparities can be an attractive differentiator for diverse talent. There is no ethical reason consistent with DEI policies that would justify differentiated pay levels for any role based on an individual’s diversity characteristics.

T&C are not only about finances. Other factors such as job location, opportunities for remote work, vacation time, parental policies, flexible work hours and retirement policies are just some of the criteria candidates have told us matter to them. These factors’ importance varies based on personal circumstances and diversity characteristics of candidates. Organizations should consider both financial and nonfinancial components when constructing job offers. Attempting to apply a one-size-fits-all approach to T&C can negatively impact a candidate’s decision to accept an offer. A “zero flexibility” policy on T&C signals a desire for conformity and is inconsistent with the core principles of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) and the need to welcome diverse talent.

The First 180 Days

You have made a diverse hire! Integration is including the new hire in your team, organization and culture without the pressure to conform and lose one’s individuality. Assimilation is an absorption into these same constructs but with the loss of or denial of one’s own identity. Individuals and organizations should seek integration, not assimilation. It’s impossible to precisely determine the degree to which someone is integrated versus assimilated. It is a continuum, and where an individual will eventually land can vary depending on their own personality, tenure in the organization and topics they feel confident or passionate about. It’s also dependent on the host individuals, team, organization, culture and ways of working, and how they might evolve with the addition of the individual into the mix.

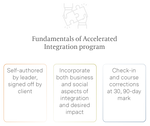

Most major companies have onboarding programs to help individuals settle in. They also increasingly have special programs to aid the inclusion of diverse leaders by plugging them into relevant support communities or networks. Onboarding programs are about the “work,” while DEI programs are about the social aspects of integrating into a company, and the two are often designed and delivered by different teams. What is needed is a combined program of accelerated integration that does not treat the work and social aspects of integration as separate, but as interlinked and mutually reinforcing. Our HBR article “New Leaders Need More Than Onboarding” is a good starting point of what a customized program could look like for a new leader.

Self-authorship is an important component of impact, satisfaction and integration. A program is likely to have elements of self-awareness, the team, wider stakeholder groups, the culture and elements of taking charge purposefully in terms of quick wins, operational impact and strategic alignment. The first 180 days are crucial in this regard and should involve check-ins at days 30 and 90 to ensure that the leader is landing and integrating in line with expectations, issues flagged, open items aligned on, and necessary interventions and support introduced as needed.

The minimum objective is to seek retention, development and performance outcomes from diverse leaders that are consistent with the rest of the organization in every material sense. The aspired objective is to increasingly experience the enhanced value that making a diverse hire enables—it starts once the new individual feels included, enabling positive benefits across the full range of business activities, including the way conversations are held, decisions are made, the organization is led, customers are approached, commercial outcomes are sought, society and stakeholders are engaged, and more.

The natural progression of this integration across multiple diverse leaders is the evolution of new norms, news ways of working and eventually a new culture.

Click on each of the boxes above to learn more of what the new proposed gold standards under Search 2.0 are